Given the emphasis now placed on the speed of computers and the incredible gains of

Moore’s Law, one might presume that the primary issue with the computers of the 1950’s was that they were

slow. Computers were already much faster and more reliable than any human being could hope to be. Lack of

processing power was not necessarily the bottleneck here.

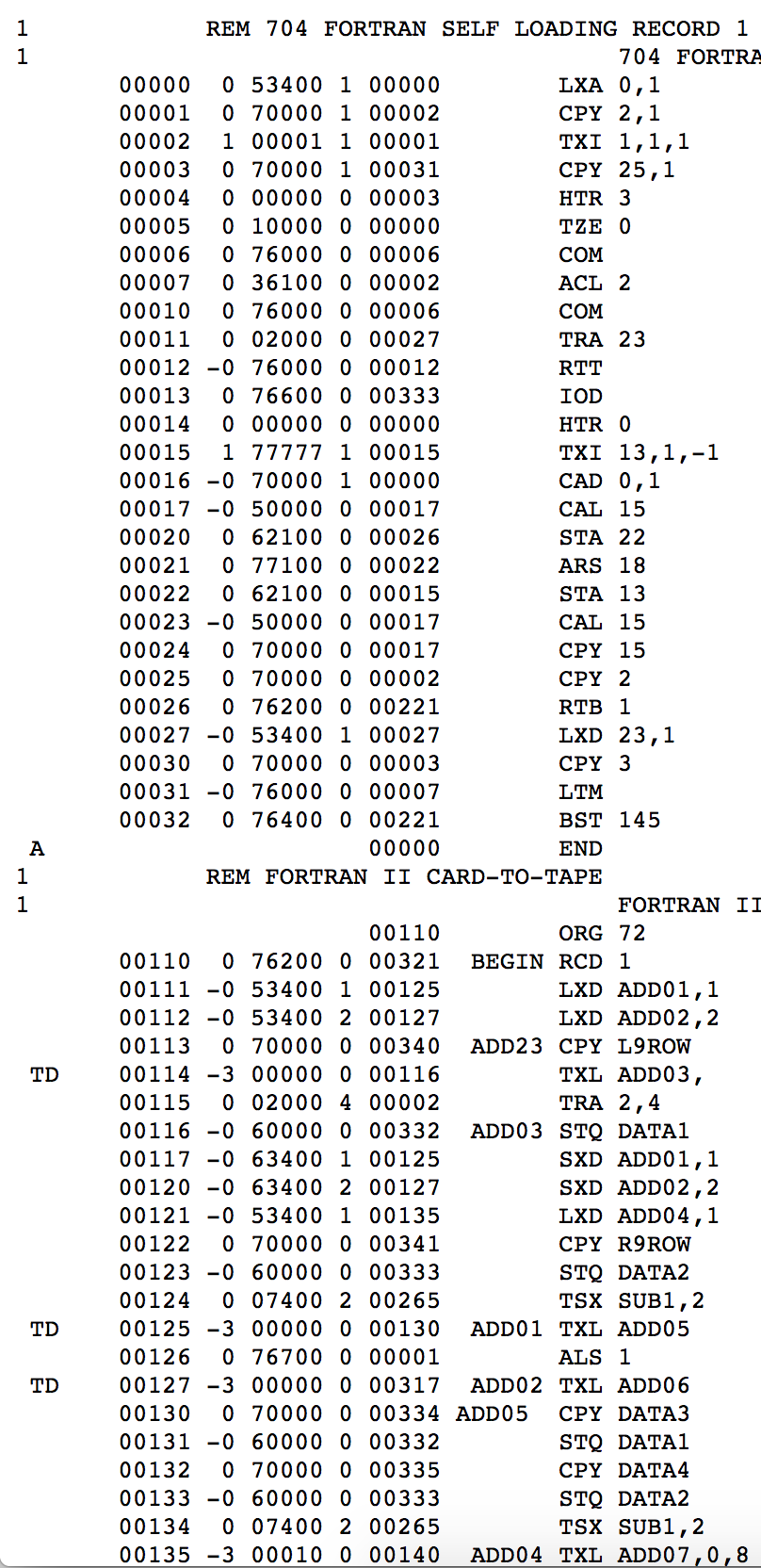

Part of source for the Fortran II compiler.

Part of source for the Fortran II compiler.

One major problem that Professor

Philip Morse identified was the input and output, as computers back

then didn’t have a screen and a keyboard. Programs had to be converted to punch card by human, which is bound to

introduce errors. And if the output required more than printing a few numbers, the results would have to be

printed to magnetic tape (which blocked the computer), then converted to punched paper tape by a slow mechanical

device, and then converted into human-readable format by an automatic typewriter. Or, one could display the

results on a cathode-ray tube, take photographs of each screen, and then manually transcribe the photographs by

hand to a more legible form.

This input/output issue was especially problematic for debugging. In modern times, one of the first things the

beginner computer science student learns is to inject

print statements all throughout their code to

figure out where things break down. For the more advanced, debugging is simplified by tools that allow

one to insert breakpoints and view the entire state of the program as it runs. Not so in the 1950’s. The only

way to figure out what was happening inside a defective program was to halt the program prematurely and slowly

wait for the computer to print out all the values, and hope that one of them will point to the origin of the bug.

For those not familiar with coding, this is a little like trying to figure out what's wrong with a car without

lifting the hood up. The logical thing to do would be to write the program in sections, but computer time was

expensive and highly on demand, as everyone on campus had to share the same computer, and nobody would tolerate

someone holding up the queue as they spent several hours writing the next segment of code while the computer idled.

Thus, it was recommended that one write the entire program in "one continuous unit" (printing out few

values, which might be helpful for debugging, due to the slow output). This is a little like trying to

build a car without testing any of the components until the entire car has been assembled. And all of this was

done in assembly language, the most low-level and difficult of coding languages to use, and without the aid of

even a basic text editor like Vim.

Thus, to quote Philip Morse (emphasis mine),

“At present, the writing of a program for a large computational problem, checking it out and determining the

accuracy of the final answers, is the biggest bottleneck of all in the use of the really fast computers... We have

adopted the rule of thumb that any computation which can be completed by hand with an expenditure of

less than about three man-months of time, and which won't be repeated sooner than a year, should not be

programmed for Whirlwind. We have found by experience that the answers to such problems can usually be obtained

quicker by hand, because a new program, for a tough problem, can easily take more than three man-months to perfect.”

So no using the computer to do your math homework. The machines at MIT were reserved for only the most

tremendous and humanly impossible of calculations. Although Morse thought that the problem was "inherent in

the very nature of the machine," the immense cost of debugging was one of the motivations for

the development of Fortran, one of the first compiled languages, which would greatly reduce the difficulty of

programming solely in assembly. Today, as computers have changed from complex machines operated only by

specialists to devices intended for the nontechnical, user interfaces have become their own field, and entire

companies have risen up around developing

IDE's

to aid programmers with development.

If you want to try your hand at programming the computer yourself (albeit with many more tools), try out our

simulations!

Original document here.